When I last posted "News from Eden," I shared my desire to write a biography of Father Louis J. Twomey, SJ. Today I am grateful to let you know that I am currently completing a monthlong research trip to New Orleans as the first official stage of my endeavor to tell Twomey's story. Twomey's papers are in the Loyola University New Orleans Special Collections and Archives, which I have been blessed to research while enjoying the gracious hospitality of the university's Jesuit Community. My travel expenses have been covered by a private donor and by The Jesuit Social Research Institute in collaboration with the Loyola University New Orleans College and Arts and Sciences.

Based on my experience writing Father Ed: The Story of Bill W.'s Spiritual Sponsor, I estimate that writing my Twomey biography—tentatively titled God's Gadfly—will take me about a year. Since the funds that I have raised thus far extend only to my present research trip, and since any publishing contract that I may obtain will probably cover only a few months' expenses, I will need to do more fund-raising to make up the difference. So, after I return home to Washington, DC, on September 9, I plan to post an online fundraiser. If you would like to be notified when the online fundraiser goes live, or if you would like to offer support independently of it, please write me at the email address at the bottom of my Biography page.

Currently I am working on a proposal for God's Gadfly that will include an overview and an annotated chapter online. The overview is complete and I am pleased to share it with you—see below. Last, if you live in Texas, Massachusetts, Vermont, or New Jersey, I'll soon be coming your way to speak on Father Ed, so do please take a look at my speaking schedule and come if you can. Thank you and God bless you!

God’s Gadfly: The Life and Witness of Southern Civil-Rights Pioneer Louis J. Twomey, SJ

"I am tired, but I always find time to follow Father's suggestions." — Martin Luther King, Jr., writing to Henry J. Engler Jr., about Father Louis J. Twomey, SJ, December 10, 1964

“Jesuit Father Louis Twomey ... has done more than any one man hereabouts to translate Catholic social principles into meaningful action.” — Walker Percy, “New Orleans Mon Amour,” Harper’s, September 1968

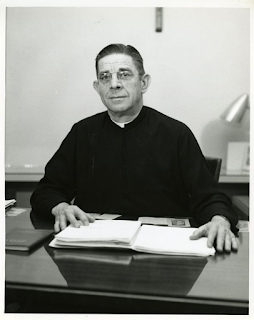

Father Louis J. Twomey, SJ, was a classic, cassock-wearing old-school Jesuit—but with a twist that made him stand out among Catholic clergy in Louisiana, where he ministered from the late 1940s until his death in 1969. He crusaded against atheistic communism, gave retreats, prayed the rosary, paused work at noon to lead his staff in the Angelus, began each car trip with a prayer, never sat beside a woman on a train (for fear of causing scandal) ... and fought white supremacy. With God’s Gadfly: The Life and Witness of Father Louis J. Twomey, SJ, the Christopher Award-winning biographer Dawn Eden Goldstein (author of Father Ed: The Story of Bill W.’s Spiritual Sponsor) will present the first full-length biography of this great-souled Jesuit who successfully challenged his religious order—and humanity at large—to put its belief in human dignity into action.

Inspired by the social-justice encyclicals of Leo XIII and Pius XI, Father Twomey felt a powerful calling to champion the rights of organized labor, the poor, and African-Americans suffering injustice in the segregated South. In 1947, he founded the South’s only labor school, the Institute of Industrial Relations at Loyola University in New Orleans. The following year, he began publishing Christ’s Blueprint for the South, a monthly newsletter sharing his vision of social justice with fellow Jesuits around the world. Its credo: “to create a society in which the dignity of the human person, in whomsoever found, shall be acknowledged, respected, and protected.”

It was a time when Jesuits wielded outsize influence in the Catholic intellectual world and beyond—and the Blueprint influenced the influencers. Over the twenty-one years of Twomey’s editorship, the subscriber base of the newsletter—renamed Blueprint for the Christian Reshaping of Society—grew to encompass three thousand Jesuits in forty-four countries. Among its readers was Ian Travers-Ball, who credited the Blueprint for inspiring him to serve the poor in India with Mother Teresa; as Brother Andrew, he became the first superior of the Missionaries of Charity Brothers.

Although scholars often acknowledge Twomey's accomplishments, the only published study of his life until now was the slim 1978 monograph At Face Value, by former America editor Father C.J. McNaspy, SJ. At Face Value was adapted from a dissertation, and it read like one. It conveyed Twomey’s importance but failed to capture his fire. Now, fifty-five years since his death, and two years since the New Orleans City Council Street Renaming Commission voted to rename Calhoun Street “Father Louis J. Twomey Street,” the time is right for a biography worthy of him.

God’s Gadfly will detail the breadth of Twomey’s apostolic labors, which eventually extended to include the Inter-American Center, a leadership-training program that taught democratic principles to more than 1,000 young professionals from Latin American countries. But its special focus will be upon his visionary work in civil rights, including his newly discovered correspondence with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Father Twomey’s passion for justice led him to become one of King’s earliest white allies, as well as the first Catholic priest to offer the young minister both moral and material support. The two became friends during a visit of King’s to New Orleans in early April 1954, before King completed his doctorate and even before he pastored a church. For more than a decade, Twomey would advise King on Catholic issues and provide him with literature to help him persuade Catholics of their obligation to pursue racial justice.

Many Catholics needed persuading. Formed in an age of populist demagogues such as Father Leonard Feeney and Father Charles Coughlin, these members of the faithful correctly grasped that Catholicism stood in opposition to communism. But they felt no religious obligation to oppose racial prejudice. Among them were thought leaders such as National Review’s William F. Buckley, who went so far as to portray the fight against segregation as a dangerous distraction from the fight against communism.

Father Twomey confounded complacent Catholics by insisting that white supremacy, in presenting America to the world as a land of inequality, only served to fuel communism’s spread. To Buckley, such an argument was “nonsensical.” Others used harsher words. Father Twomey told a 1953 Teamsters gathering that white supremacists called him a “Red in Robes” (the “robes” being his cassock), a “racial fanatic,” a “dangerous man,” and a “n----- lover.” He added that he did not fear such “intemperate epithets. But he did fear that “the gross injustices which are inherent in our interracial relations in the South” would bring down “the avenging wrath of an angry God.” As he put it in a 1950 speech to Catholic educators, “How long is God going to allow his image and likeness in black skin to be kicked around?”

By far the most painful opposition Twomey faced was from members of his own Jesuit community. From 1950 onward, he tried repeatedly to convince Loyola New Orleans to admit talented Black candidates to its law school, finally succeeding in 1952 with the admission of Norman Francis (who would become the first Black president of Xavier University of Louisiana). In the Jesuit residence where he lived, Twomey’s neighbors included pro-segregation priests who resented him as a troublemaker. One of them complained to the provincial superior that, thanks to the influence of Twomey and his colleagues, young Jesuits studying at Loyola “had racial equality pumped into them.”

But Twomey persisted, and was ultimately vindicated in the most dramatic way possible.

In 1967, Jesuit Superior General Pedro Arrupe summoned him to Rome to be the main drafter of “The Interracial Apostolate,” a letter to the U.S. Jesuits urging them “to preach, to teach and to practice the Christian truths of interracial justice and charity.” The Jesuits’ present work promoting those truths can be directly traced to the influence of that letter—the first under Arrupe’s name to emphasize what would become known as the preferential option for the poor.

Two years after Twomey drafted “The Interracial Apostolate,” as he lay dying of emphysema, Arrupe wrote from Rome to encourage him: “You know how grateful I am for your wonderful work.” Indeed, as God’s Gadfly will show, lovers of justice, democratic freedoms, and Christian faith in action have much reason to be grateful for Twomey’s prophetic witness.

Contact Dawn Eden Goldstein through the email address at the bottom of her Biography page.

Contact Dawn Eden Goldstein through the email address at the bottom of her Biography page.